Chay didn't start trendy. It started serious.

In many Vietnamese households, vegetarian eating was never a "diet". It was a practice.

For centuries, many Vietnamese Buddhists have practiced ăn chay as part of a spiritual discipline rooted in compassion and restraint. For some, it's lifelong. For others, it's cyclical. They eat chay on ngày rằm (usually the 1st and 15th days of the lunar month), during Tết (Lunar New Year), ancestor remembrance days, mourning periods, or other sacred times.

But religion isn't the only reason Vietnamese people eat vegetarian food.

There's also the "quiet bargaining" side of it - the very human part.

A lot of people eat chay when they're praying for something like: an exam to go well, a parent to recover, a business deal, a new job... It's not loud, or trendy, or announced. It's just a form of devotion that shows up in daily life.

And because chay was tied to intention, not preference, the cuisine evolved with seriousness. It wasn't made to "replace meat". It was built to feel complete without it.

Temple kitchens, then, became training grounds for an entire craft: developing broths from dried mushrooms, daikon, and roasted vegetables. Texture came from frying tofu before braising it. Brightness came from herbs, pickles, and acidity. These methods shaped vegetarian food into something structurally satisfying, not symbolically symbolic.

For generations, this remained its clearest role: present, respected, but tied to specific contexts.

Everyday Vietnam: why plant-based food already fits

Vietnamese vegetarian food works because Vietnamese meals were never built entirely around meat to begin with.

A typical everyday Vietnamese meal is served with rice, vegetables or herbs, soup, and savory dishes placed on the table together and shared. Protein is always present, but not always dominant. A few slices of pork, some fish, or a small bowl of minced meat is meant to come together with everything else, not the center of the meal.

That's partly cultural, but it's also practical.

Vietnam has always been shaped by agriculture with rice fields, seasonal produce, herbs grown right outside the kitchen. So even in non-vegetarian meals, vegetables and plant-based ingredients already take up most of the table. When meat is removed, the meal doesn't fall apart.

That’s why vegetarian versions of established dishes like phở chay (vegetarian phở), bánh mì chay (vegetarian baguettes), or cơm chay (vegetarian rice) feel continuous rather than separate or "special diet food". They follow the same logic as their meat-based versions - broth still provides depth, herbs still provide contrast, Texture still defines satisfaction. When done well, nothing feels missing because nothing essential was built around meat to begin with.

Vietnamese vegetarian food also avoids one common trap of modern plant-based cooking: overcompensation. It doesn’t drown vegetables in heavy sauces or rely on dramatic substitutions to prove a point. Flavor comes from mushrooms, fermented soy, slow-cooked vegetables, fresh herbs, and contrast.

The result is food that feels familiar, filling, and complete. Not something you eat because you can’t eat meat, but something you eat because it already works.

If chay was always here, why does it feel more visible now?

For many families, the shift toward more frequent vegetarian eating happened gradually, shaped by age, health, and routine rather than ideology.

In my house growing up, chay was always part of life, but it belonged to specific days. My parents observed it on ngày rằm (full moon day) and mùng một (the first day of the lunar month), like many Buddhist families. On those days, the kitchen shifted. I noticed meat was disappeared, replaced by tofu, braised mushrooms, and vegetable dishes...When the day passed, everything returned to normal.

Years later, those meals began appearing more often. This time, not because of the calendar, but because of their health.

As my Mom got older, routine health checkups started to change how she thought about food. Like many people her age, she was told to eat lighter, to be more careful about cholesterol, to think long-term. Instead of changing her entire diet, she leaned into something she already knew how to cook. The same chay dishes she once made a few times a month started appearing regularly on the dinner table.

"I feel lighter eating like this", she told me. "Not heavy, not tired after meals. And when the doctor said my numbers improved, it gave me even more reasons to continue."

By the time it reached my generation, chay became more visible for a simple reason: it started appearing everywhere we already chose food. Urban schedules meant fewer people went out to fixed lunched spots and more people order from their phones. Delivery apps placed vegetarian dishes next to meat ones, making them part of the same everyday choices instead of something separate.

Wellness awareness reinforced this shift. We, younger consumers, began to pay more attention to how food affect our energy, digestion, and long-term health, and feeling lighter. Vegetarian meals aligned naturally with these concerns, offering familiarity without heaviness.

Growing awareness around environmental impact and animal welfare also influenced how younger consumers think, making vegetarian food feel less like tradition and more like a normal, responsible option.

Digital commerce amplified all of this. As more restaurants offered vegetarian options and more consumers ordered them, visibility increased. What changed was how people place it directly inside everyday routine: through family kitchens, doctor's advice, delivery apps, urban schedules, wellness culture...

Chay didn't suddenly become part of Vietnamese eating. It simply stopped being confined to specific moments.

What's next: market signals that are already measurable

Economic data now reflects what daily life already shows: vegetarian and plant-based consumption in Vietnam is expanding steadily, driven by normalization rather than novelty.

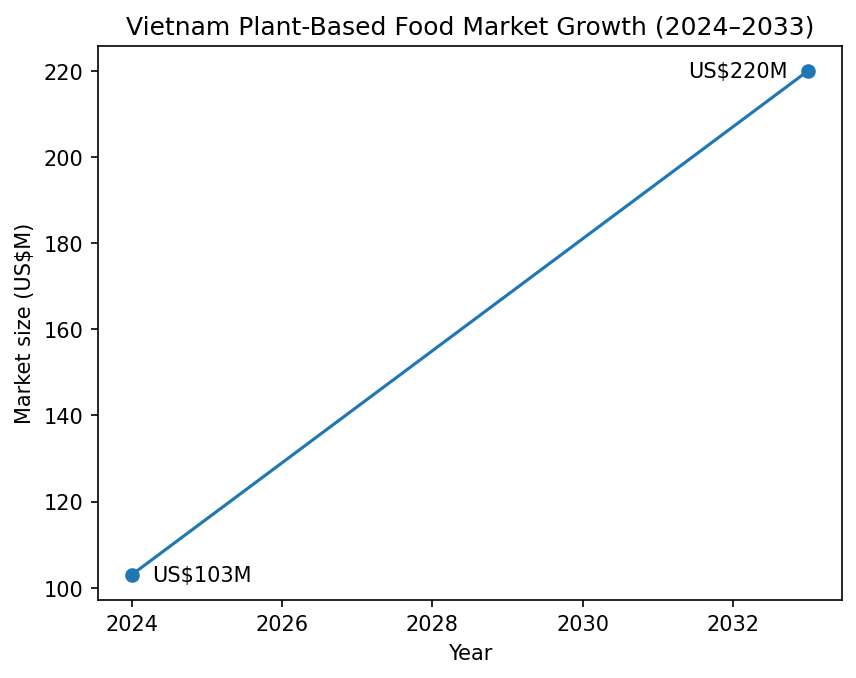

Vietnam’s plant-based food market was valued at approximately US$103–112 million in 2024 and is projected to exceed US$220 million by 2033, growing at an estimated annual rate of around 8%. This trajectory reflects sustained behavioral change rather than temporary experimentation.

Beverages have emerged as the category’s strongest entry point. Soy milk, coconut milk, oat milk, and other plant-based drinks integrate seamlessly into existing routines — coffee, breakfast, and convenience consumption. Their growth reflects ease of adoption rather than ideological commitment.

Consumer behavior indicates increasing frequency rather than exclusivity. Many consumers incorporate vegetarian meals regularly without identifying as vegetarian. This pattern aligns with Vietnam’s historical approach to eating, where dietary variation already existed within routine life.

Price sensitivity remains present, but value perception is equally important. Consumers show willingness to pay more for products perceived as safer, traceable, or aligned with health priorities. This dynamic favors producers who emphasize quality and trust over novelty alone.

Preferences continue to center on recognizable ingredients: tofu, vegetables, legumes, and traditional soy products. Highly processed substitutes occupy a smaller role, reflecting cultural preference for ingredient clarity over simulation.

Technology has accelerated accessibility. Digital commerce platforms have integrated vegetarian food into everyday ordering systems, allowing consistent availability across urban and provincial markets. This infrastructure supports repetition, which ultimately defines habit.

At the same time, manufacturing improvements are expanding product stability, shelf life, and distribution capacity. Traditional soy-based foods coexist with newer formats designed for modern retail, allowing the category to scale without abandoning its foundations.

Geographically, vegetarian food is no longer confined to major cities. Dedicated vegetarian restaurants and plant-based offerings now operate across most provinces, reflecting broad integration into national food culture.

Ho Chi Minh City, in particular, has gained international recognition as a vegetarian-friendly destination, reflecting both historical depth and contemporary visibility.

These developments do not represent a break from tradition. They represent its expansion under new economic and technological conditions.

1️⃣ Market growth: Is this market real?

=> Yes - the growth looks real and structural, not seasonal

Vietnam's plant-based market is on a steady climb, valued at US$103-112 million in 2024 , and could exceeded US$220 million by 2033, growing around 8% annually . This isn't trial behavior. It's long-term momentum.

Vietnam's total plant-based market growth (2024 → 2033)

2️⃣ Beverage growth: Where the money moves first?

=> To beverages, they are the easiest entry point

Non-dairy drinks made from soy, coconut, nuts, and oats are the lowest-effort entry point. They don't feel like substitutes, they fit naturally into daily routines (coffee, breakfast, and convenience-store stops...), driven by health awareness, lactose intolerance, and a preference for lighter, lower-calorie options...

Vietnam's plant-based beverage market is estimated at ~ US$165M in 2024 and could reach approximately ~ US$318M by 2033 , growing at about 6,73% during 2025-2033 .

More importantly, beverages already outweigh the rest of the category.

.png)

Vietnam Plant-Based Market: Food vs Beverages (2024 vs 2033)

3️⃣ Consumer behavior: Is plant-based becoming everyday? And what's actually driving it?

=> It's becoming routine, first through wellness, then ethical values starting to shape choices

Surveys show 45% of Vietnamese consumers eat vegetarian meals multiple times a week , mainly for wellness, digestion, and long-term health . Among younger urban consumers, around two out of three Gen Z and Millennials are actively trying to include plant-based or organic foods in everyday meals.

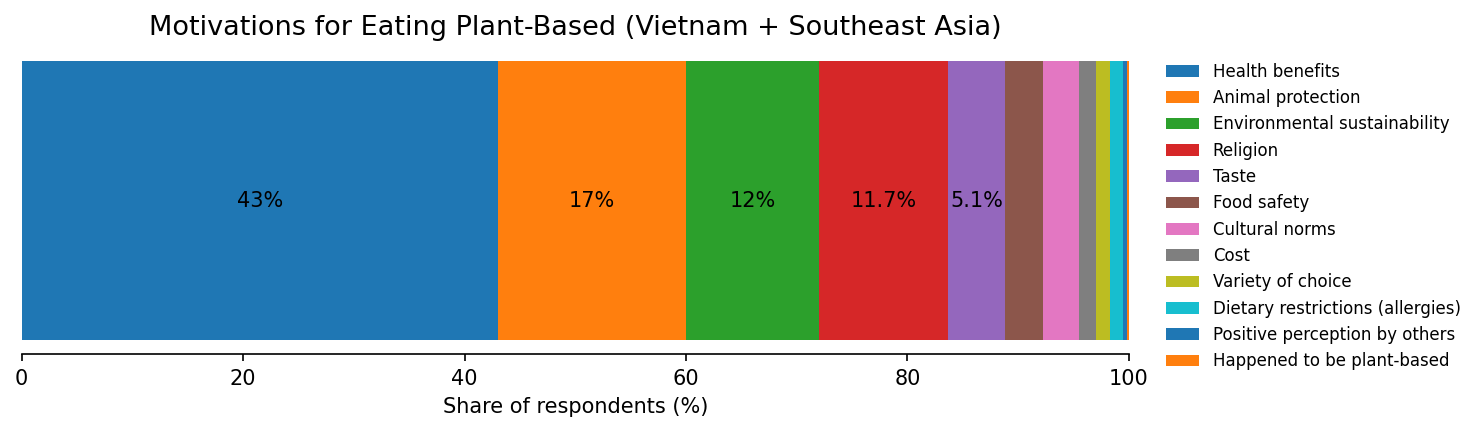

At the same time, recent consumer data across Southeast Asia , including Vietnam, show that alongside health as primary driver (43%), protecting animals (17%) and environmental concerns (12%) are already influencing food decisions.

That means, Vietnam's plant-based growth is entering a second phase. Wellness creates the habit, ethical and environmental values deepen commitment. That combination is what turns occasional behavior into long-term lifestyle adoption, especially in cities.

Motivations for Eating Plant-Based of Southeast Asia + Vietnam (Full Breakdown)

4️⃣ Price sensitivity: Are Vietnamese consumers price-sensitive or value driven?

=> They're price-aware, but willing to pay for trust

Vietnamese consumers aren't just price-sensitive, they are value-sensitive. According to a 2024 PwC survey , 80% of shoppe are willing to pay a premium for sustainability produced goods, and on average they'll spend nearly 10% more on organic products that meet environmental criteria.

A separate report found that 72% of Vietnamese consumers are willing to pay more for green products, showing broad interest for sustainability, while a nationwide survey highlighted consumers' readiness to pay extra for high quality, traceable and health oriented Vietnamese products.

In practice, this is separating the market into two paths: price-first, undifferentiated products are starting to struggle, while well-positioned plant-based brands, certified organic store, and higher-quality local producers are gaining traction through trust, traceability, and perceived safety.

5️⃣ Ingredient preference: What do people actually want to eat?

=> Ingredients - not heavy substitutes

As plant-based becomes part of everyday life, preferences are getting simpler. Flexitarian consumers increasingly reach for vegetables, tofu, salads, and nut milks , while heavily processed mock meats are losing appeal . This mirrors Vietnam's existing food culture: balance, freshness, and ingredients over replacements.

6️⃣ Tech and infrastructure: How does plant-based scale in Vietnam?

=> Through technology improving both delivery and production, not storefronts alone

Vietnam's digital retail boom is affecting how people access plant-based food.

The retail e-commerce market exceeded roughly US$24 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at around 23% annually through 2027

, as more shoppers move everyday purchases online. Online grocery and FMCG categories, where plant-based food naturally sit, are a major part of that momentum,

valued at US$3,1 billion in 2025, and with online grocery market alone forecast to reach US13,4 billion during 2026-2032

. as platforms like GrabFood, Shopee, ShopeeFood, BEfood and XanhSM streamline logistics and checkout, plant-based products become easier to discover and repeat-purchase - not just in big cities but across provincial markets. This broad digital shift is making plant-based eating less about destination dining and more about on-demand consumption, accelerating everyday adoption alongside the general rise of online grocery and retail shopping habits.

At the same time, food manufacturing is quietly upgrading plant-based food from inside out. Improvements in texture, longer shelf life, and more consistent in flavor are changing tofu, soy products, and making space for newer formats like TVP (textured vegetable protein), and plant-based dairy. The shift goes beyond better products, it’s moving plant-based food from traditional soy staples toward next-generation meat and dairy alternatives designed for modern retail and wider distribution.

7️⃣ Geographic expansion: Is plant-based still an urban niche - or spreading nationwide?

=> It's expanding geographically, with Ho Chi Minh City gaining global visibility

Vegetarian restaurants now operate in 51 of Vietnam’s 63 provinces , with plant-based options present in nearly 80% of locations nationwide , reflecting broad adoption beyond major metros.

At the same time, Ho Chi Minh City is becoming increasingly visible on the global stage, appearing repeatedly on PETA's World's Most Vegetarian-Friendly Cities list. The city was first mentioned as a rising destination, later gained consistent recognition, and most recently entered the Top 10, according to Plant Based News .

Together, these signals suggest Vietnam's vegetarian scene is no longer a niche urban trend, it's expanding geographically and gaining global attention.

Conclusion

Somewhere along the way, chay stopped standing apart and settled quietly into the fabric of everyday Vietnamese eating, no longer defined by occasion or intention. It isn’t treated as an alternative or an exception, but simply as one of the many ways a meal can exist, shaped quietly by the same rhythms that have always shaped how Vietnam eats.